Cats are amazing animals: individual, acrobatic, daring, mysterious. But they are cats, and always will be. A dog, on the other hand, is like us. Whether they think of us as dogs or of themselves as humans, we don’t know, but we both feel that we are pack mates. In the human pack, of course, these descendants of wolves, retaining childish (puppy) traits, are forever subordinate.

Source: Henri Breuil, Wikipedia

Man’s best friend has changed quite a lot since his wolf days, and not just in appearance. Csányi Vilmos1 writes somewhere that “Dogs are artificial animals, very different from wolves.” Following in the footsteps of the Hungarian ethologist, entire institutes are now specializing in research into the behavior of dogs. We could call it the first genetic experiment: our ancestors bred wolfes until they became greyhounds, foxterriers or Pekingese. This mania had some negative spin-offs — it was high time to ban the breeding of certain defective breeds. The fault of fighting dogs is a psychological one: from these breeds the inhibition of wolves to attack a surrendering opponent has been eradicated. Anyone who has owned a dog knows that every breed has a different psyche, and of course individuals within a race can be quite different.

A descendant of wolves

Dogs are wolves and yet they are not. Their metabolism has changed: they can digest more plant matter. They can still procreate with their ancestors, but they think differently. In the right circumstances, as the case of the dingo demonstrates, they can revert to the wild. Research suggests that the dingo was brought to Australia by a group of people migrating from Southeast Asia around 3-4,000 years ago. The aboriginees first conquering the continent some 60,000 years ago didn’t have dogs, as wolves weren’t domesticated (according to current knowledge) until 15 to 40,000 years ago. The ones brought by the later arrivals then became independent, a separate lineage. No one knows how many marsupial species they wiped out in their time, but today, as the continent’s top predator, they’re keeping the troublesome army of escaped cats, introduced foxes, rabbits and other placental mammals somewhat in check. Where they still occur, that is, as sheep farmers have drastically reduced their numbers. Dingoes kept as pets are not quite like other dogs, they are more wary of humans, more independent, in some ways more sophisticated.

A partially or wholly dingo pet dog in Australia.

Between stray and domestic dogs there is a lot of going back and forth. In many Western countries, stray dogs have largely been taken to the pound, but in most of the rest of the world there are large numbers of semi-independent dogs living in close proximity to humans. In Georgia, for example, a friendly stray may spend a whole day with you and, although happy to receive handouts, doesn’t exert any pressure, simply enjoying your company.

Whether humans domesticated wolves or wolves domesticated humans is a matter of opinion. As many have already stated, it’s not us who are fed by dogs but vice versa. One way of thinking about it is that two species formed an alliance based on similarities in social structures. Some researchers believe that early humans may have learned hunting techniques from wolves, who are not exactly simple-minded animals. In Transylvania, where huge dogs guard sheep flocks, wolves often trick the dogs. Two of them may appear from upwind. The dogs, of course, give chase. The wolves flee just fast enough to make it worth while being pursued, luring the guardians away. The sheep left unprotected are then preyed upon by the rest of the pack, who come from downwind, remaining undetected.

Dogs in the human world are clearly the underdogs. Expressions in all kinds of human languages show the difficulty of dog life. It’s a dog-eat-dog world for them. They have une vie de chien. Amores perros. Hundeelend. Let’s face it, many a village mutt today still spends a life on a chain. Even though chaining has been banned, it still happens today, which is particularly brutal for an animal that was made for long distance running. Kennels and tiny enclosures of the yard are also cruel. In fact, if you don’t spend a lot of time with this social creature, keeping a single one is inhumane as well. By their old age, many dogs become quite grumpy, although this depends on the breed. Chains certainly don’t help.

Source: ma7.sk

The fact that this loyal friend is still used for experiments is astonishing. In the post Is Meat Murder? the documentary Earthlings is mentioned, exploring the treatment of animals. While it’s generally better to stay on the positive side of things, I believe it’s useful to be aware of certain phenomena in society. Having posted that this is one of the few horror films that must be watched till the end, I reluctantly made myself watch it. I could only do it in several parts, counting the minutes remaining. One of the scenes that burned into my mind was of a cute experimental dog, terrified, trying to make friends so he wouldn’t be tortured. I don’t yet know what to do about animal testing, but it’s not right.

Lapdogs with their fancy dresses and jewelry are at the other end of the scale. While our friend Canis domesticus shares many qualities with humans, this shouldn’t be taken too literally. It’s somewhat doubtful that doggies in bridal gowns fully grasp the spiritual significance of what’s happening. In Hungarian there’s a saying: dogs don’t become bacon, meaning things can’t change their basic nature.

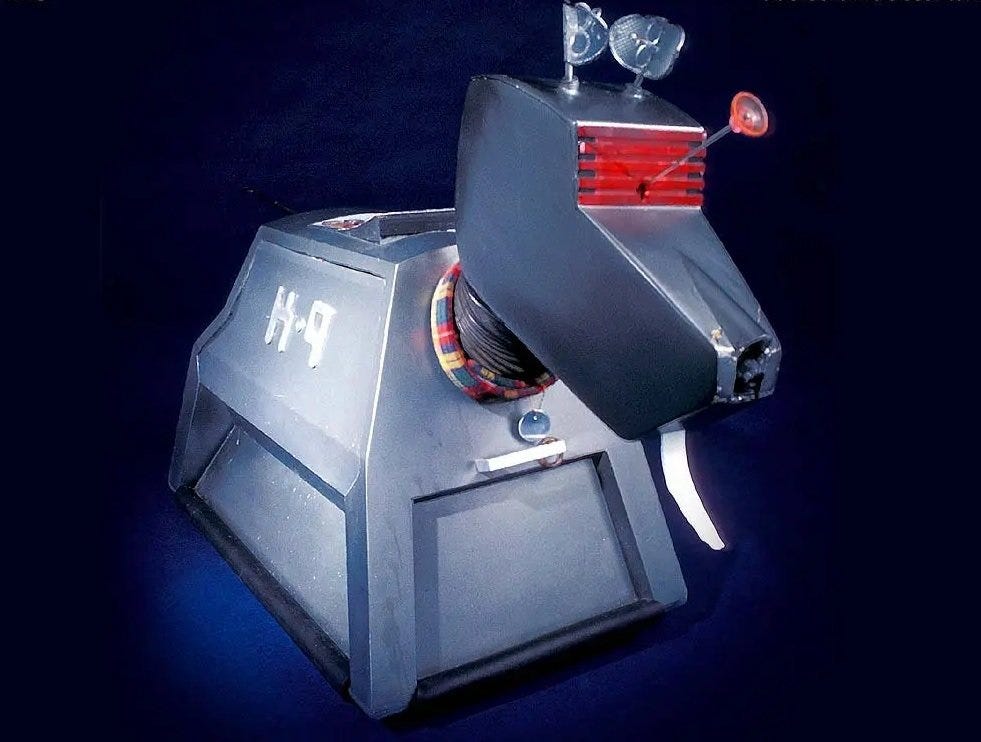

Then there’s K9 (Canine), the robot dog, appearing in Doctor Who from many decades ago. Metalhead, an episode in Black Mirror displays a thoroughly anti-utopian aspect of this phenomenon. Appearently, androids will also need a companion.

Source: thedoctorwhocompanion.com

White Fang, Lassie and Bogáncs2 are heroes like any other. Some dogs are main characters in literature as if they were people. The stories mostly revolve about their loyalty, their affection to their owners, their simple yet tenacious minds and vitality. While not as agile and magical as cats, dogs retain something of the mysterious side of the world. We’ve already mentioned Rupert Sheldrake’s series of experiments clearly indicating that some dogs have a sense telling them when their owners are coming home.

Living with a dog is very different from living without one. In some ways, it’s like having the family be complete. In the last 10,000 years, it’s hard to find a human culture without dogs. South African bushmen were perhaps the last group to acquire dogs, and it was only with the arrival of Bantu tribes that they come into contact with them. A rural house seems empty without a dog. And that warm presence makes even more of a difference to lonely, urban people. It’s nice to return home and be greeted by someone jumping up and down with joy just at the sight of you. And humans have probably been attracted to furry creatures since we were monkeys.

Observing our four-legged companions can add a lot to our understanding of ourselves. There are many similarities between us, although dogs are more honest. Their emotions aren’t cluttered by that chattering, conceited, restless organ that causes so much trouble on this planet — the human mind. While dogs can be a little sly at times, they are basically good creatures. As are we, despite all appearances to the contrary.

It’s just that sometimes our own structures hinder our clear vision…

Source: Puli1989, Wikipedia

Csányi Vilmos, born 1935, is a Hungarian ethologist, academician and writer. He started studying the behavior of domestic dogs in the nineties.

Bogáncs (‘thistle’), a pumi (small Hungarian sheep dog), is the main character of Fekete István’s novel of the same title. Following the communist takeover Fekete was tortured after which he largely stopped writing about people. He developed a genre the like of which I’m not familiar with in any other culture, writing scores of books about nature and animals. His books have been extremely popular.